At my first software industry job (Cataphora, an enterprise search and NLP startup), the CEO, Elizabeth Charnock, ran an in-house leadership training program, which was mostly just her sharing her thoughts on leadership. One of her main messages was that management was about being willing to make decisions, even though you’re probably wrong. You should try to make an informed, fair, optimal decision, but you very rarely have that privilege. Most people’s decisions are not optimal most of the time, and you should get used to, rather than fear, being wrong. The worst thing you can do in the face of incomplete information was abdicate making a decision. Being afraid of being wrong, and making the implicit or null choice was far more fatal. Her key to getting comfortable as a manager was to get comfortable making decisions even in the face of uncertainty and disagreement.

Fast forward a few years, and I was a first time product manager, in a mid-size mobile startup, where there were no other product managers or pre-existing patterns to follow. People from different functions would come ask me classic product questions, “can this product do this thing we thought of?”, “I need to tell a client this feature will be ready in a month, will it be?”,”whats the status of this bug thats annoying me?”, “can I cut this use case out, it will save days of development”… and so on… and on.

I tried to document and delegate, but when cornered, to answer questions and make decisions the best I could: informed and goal-focused. But I also remembered that leadership training. It was important to me to never abdicate a choice brought to me. Not to always have the answer, but to always be the decider or the delegator. But I also heard, and found to be true, that this was a mentally exhausting way to live. After a month or two my engagement with these small day-to-day decisions began to flag. I also read, around this time, that there is a limited amount of cognitive effort available in a given day, and decision making burns a lot of it. Some execs handle this by wearing identical clothes every day, sticking to strict life patterns, and otherwise trying to minimize the unimportant decisions they make. I decided that my way to handle this would be to take a piece of cardboard about the size of a piece of copy paper, and use a marker to write YES on one side, and NO on the other. Then, when someone came to me with a question, or decision point that I thought was basically a toss up, or where I needed to preserve my mental space and energy, I would flip the PM-o-Matic in the air, like a giant coin, and that would be my answer. Really.

I’m not sure how often it served as just the starting point to a conversation or negotiation, and how often its decisions actually stood, but I do know I felt like I was leading, but that some of the mental burden was off. Oddly, most people didn’t mind, its ridiculousness became a way to diffuse sometimes tense discussions, and mostly they were just happy to have a clear answer.

Two years after I left, I got a text from a former co-worker. It was a picture of the PM-o-matic. She had saved it after I left, and was now leaving too. She said she always appreciated my use of it to resolve questions quickly and with a sense of humor. I don’t use the PM-o-Matic anymore, and it’s certainly not something that would pass muster in a sophisticated product organization. But I’d still recommend it over making no decision.

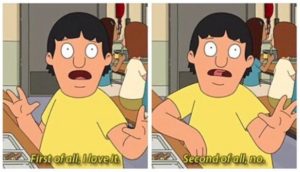

One of the hardest parts of being a PM, in my experience, is embracing the needful thing of saying no… all the time.

One of the hardest parts of being a PM, in my experience, is embracing the needful thing of saying no… all the time.